Bangui, Central African Republic — After years of insecurity and internal strife, authorities and scientists from the Central African Republic are again turning to nuclear and nuclear-related techniques for development. From increasing soil fertility to developing improved plant varieties and understanding their water resources, they are now picking up speed with the help of the IAEA and its partners.

“We’ve already suffered enough from the conflict,” said Kosh Komba, researcher at the University of Bangui, during a public health presentation he attended last month under an IAEA project. “We can’t afford to suffer more due to things we can avoid.”

When the conflict erupted in 2013, there was no common strategy to work on, said Pilar Murillo, manager of the IAEA’s technical cooperation projects in the Central African Republic. “Now, the situation is different. Together with the relevant national authorities, we have drafted a new strategy for 2017-2021.”

This article summarizes the status of the work in the country and the hopes of the scientists involved.

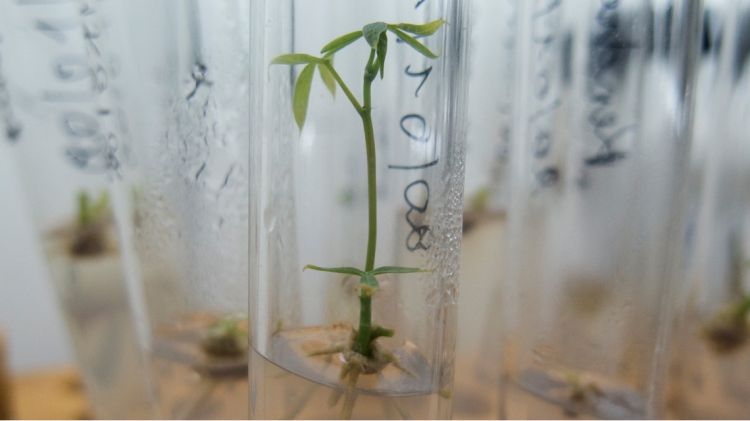

See scientists at work in the field in this photo essay.

Water

In 2010, a team of researchers at the University of Bangui started working with the IAEA to improve their understanding of groundwater using isotopic techniques. Before they were forced to freeze their studies in 2013 due to conflict, the scientists had managed to identify groundwater bodies vulnerable to pollution in the Bangui area.

Today, they are back in the field.

“Scientists in neighbouring countries can almost never go to the field to take samples because of armed rebel groups,” said Eric Foto, project focal point in central Africa. “But now we have managed to continue what we started. What we do is travel with colleagues from non-governmental organizations and take advantage of their protection. Work goes on.”