The announcement in June 2011 that the devastating cattle disease, rinderpest, had been eradicated worldwide marked the end of decades-long campaign that brought governments, international organizations, scientists and farmers together, into a global network. Spearheaded by the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) and FAO, the Global Rinderpest Eradication Programme (GREP) delivered the ultimate gift to the world’s farmers – the gift of freedom from fear of one of history’s worst animal diseases. This successful campaign, in which the Joint FAO/IAEA Division of Nuclear Techniques in Food and Agriculture and the IAEA's Department of Technical Cooperation played a key role, closes the door on one scourge. yet, the world still must deal with many other major animal diseases that require concerted efforts in diagnosis, surveillance, risk evaluation and risk management. Today, the Joint Division envisions building on the networks established during the rinderpest eradication campaign and moving ahead in

its efforts to control, prevent and eradicate other animal diseases that remain so devastating to the world’s farmer’s livelihoods.

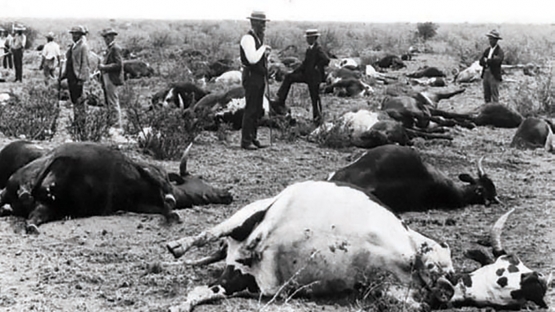

Rinderpest has been responsible for catastrophic epidemics around the world for at least the last 1000 years. Also known as the “cattle plague”, rinderpest has wiped out countless herds of domestic cattle, yak and other hooved animals as well as their wild relatives, leaving in its wake economic ruin, famine and even has been blamed for the weakening of the Roman Empire. Folklore also maintains that Genghis Khan sent rinderpest-infected cattle into the herds of his enemies to wipe out their food supply, making them easier to conquer.

The Joint FAO/IAEA Division of Nuclear Techniques in Food and Agriculture’s involvement with rinderpest dates back to the 1980s, when it added its diagnostic expertise to a vaccination programme that led to the control of rinderpest in 22 sub-Saharan African countries. Although the efforts initially appeared very successful, residual pockets of rinderpest were left, which allowed renewed outbreaks of disease. This served to demonstrate that moving from control to eradication of rinderpest would require better diagnostic tools, maintenance of a “cold chain” to ensure the efficacy of the vaccines, and a stronger veterinary infrastructure.

From this beginning, the Joint Division, with the support of the Technical Cooperation Department, working closely with other international organizations through the Pan-African Rinderpest Campaign (PARC) which began in 1987 and GREP which began in 1994, changed the focus of its animal health activities and developed programmes to promote the new enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technology. The ELISA was developed from assays that used radio isotopic tracers for the diagnosis, monitoring and surveillance of livestock diseases, but by adapting the test to a technology that utilized enzymes as markers, allowed large numbers of samples to be tested in a relatively short time with quantifiable results. Most importantly, the assays could readily be deployed to national veterinary laboratories in the form of standardized kits. This led to the development of an ELISA specifically for rinderpest detection which was distributed by the Joint Division together with investment in building capacity of the veterinary services in at-risk countries through individual and group training and workshops.