At 5 100 meters above sea level, the air around Bolivia's Huayna Potosí glacier is thin, brittle with altitude. The wind moves over the ice in long, deliberate strokes, shaping a landscape caught between endurance and erosion. It is cold but not always freezing along the mountainside.

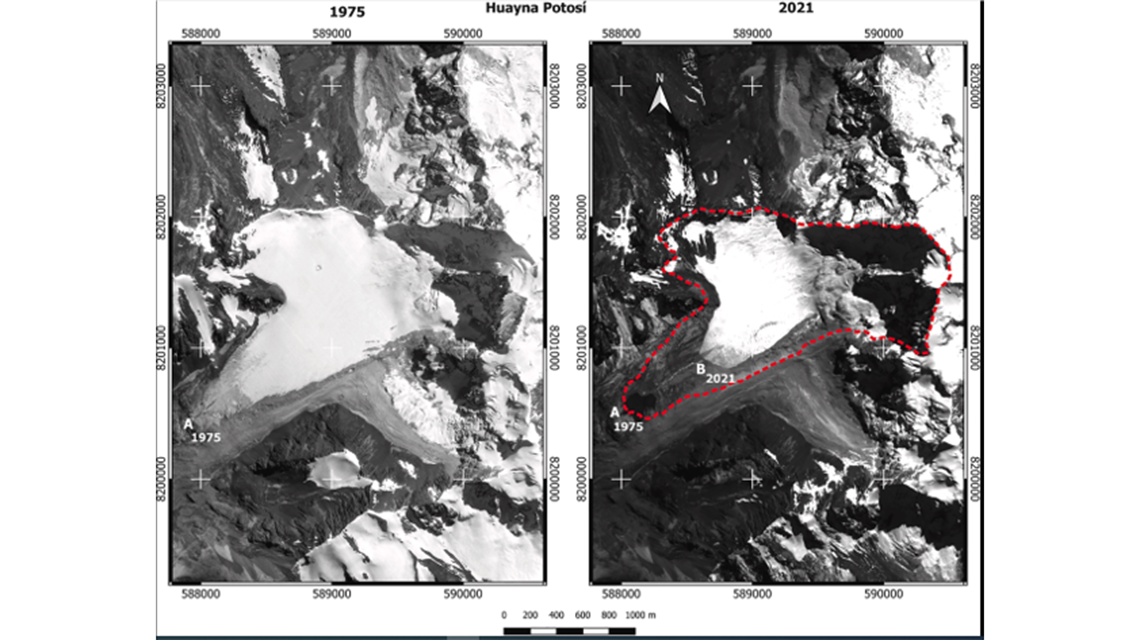

Where thick blue ice once filled the valley, bare rock now juts out like exposed bone. Year by year, the Western Huayna Potosí Glacier thins and retreats upslope at an annual rate of approximately 24 meters. In its wake, it leaves behind scattered stones and a meltwater lake, a body of water that did not exist in 1975, marking the glacier’s former boundaries.

Here, a team of scientists from the Andes and the Himalayas — representing Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, China, Ecuador and Nepal — wake before dawn to begin their ascent, knowing they must return before dark when the risk of accidents increases. The altitude makes breathing difficult, forcing them to move slowly, deliberately. They walk in single file, careful to avoid hidden crevasses that could swallow a person whole. At the centre of the glacier, they install a machine, an assemblage of panels and wires, to patiently decode the silence of the mountains.

Their work is supported technically by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) through the Joint FAO/IAEA Centre of Nuclear Techniques in Food and Agriculture, a unique partnership between the FAO and the IAEA, including logistically and financially by the IAEA's technical cooperation programme.

This cosmic ray neutron sensor is one of the two sensors, painstakingly installed by the team on the glacier, that measures easily, quickly and continuously how much water is accumulated on top of the glacier in the form of snow. This snow keeps the glacier alive. Each reading is a snapshot of the glacier's diminishing existence.

The shrinking ice means more than just disappearing landscapes—it signals upheaval for those who rely on its water. The data that the scientists are collecting from these high-altitude glaciers is helping researchers predict the cascading effects of ice loss on ecosystems and local communities in order to find ways to adapt.