Punta Cana, Dominican Republic — A group of men in sun hats gather around a cardboard trap for flies. They inspect it with their pencil-shaped UV lamp, nod and smile from time to time. These insect specialists have left their lab coats behind to help the Dominican Republic verify its success in controlling the Mediterranean fruit fly, a pest that cost the country US $40 million in lost exports last year. The men nod again, satisfied that the trap contains no wild flies.

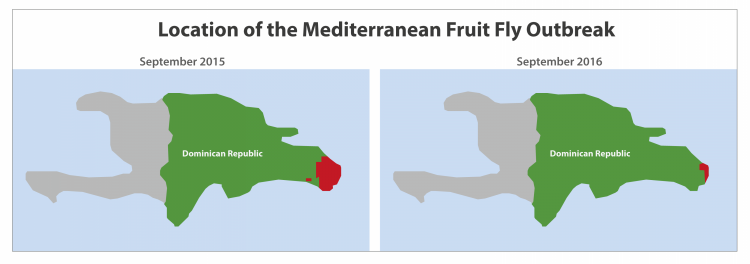

The Mediterranean fruit fly was reported for the first time in March 2015 in Punta Cana, the eastern region of the island. As soon as the government announced the presence of this pest, the United States banned the import of 18 fruits and vegetables, severely affecting the country’s main source of income after tourism: agricultural exports.

But thanks to a quick response by the Dominican Republic’s Ministry of Agriculture with the support of the IAEA, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), the outbreak was contained in just ten months. The result? In January this year, the U.S. lifted the agro-ban for most of the country.

“It was disastrous,” said Pablo Rodríguez, financial manager of Ocoa Avocados, the country’s number one exporter of green king avocado. “Almost all we do is export, so you can imagine our loss. We had our product ready by March, when the ban started. We lost all that and our next cycle of production, too. Just because of a few flies, we all had to pay.” Ocoa Avocados’ losses amounted to US $8 million.

For us, it became a trauma. I would go to sleep thinking of the fly, I would dream of the fly, and in the morning, I would wake up with the fly in my mind.